- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Life of the Gila: Hohokam Worlds

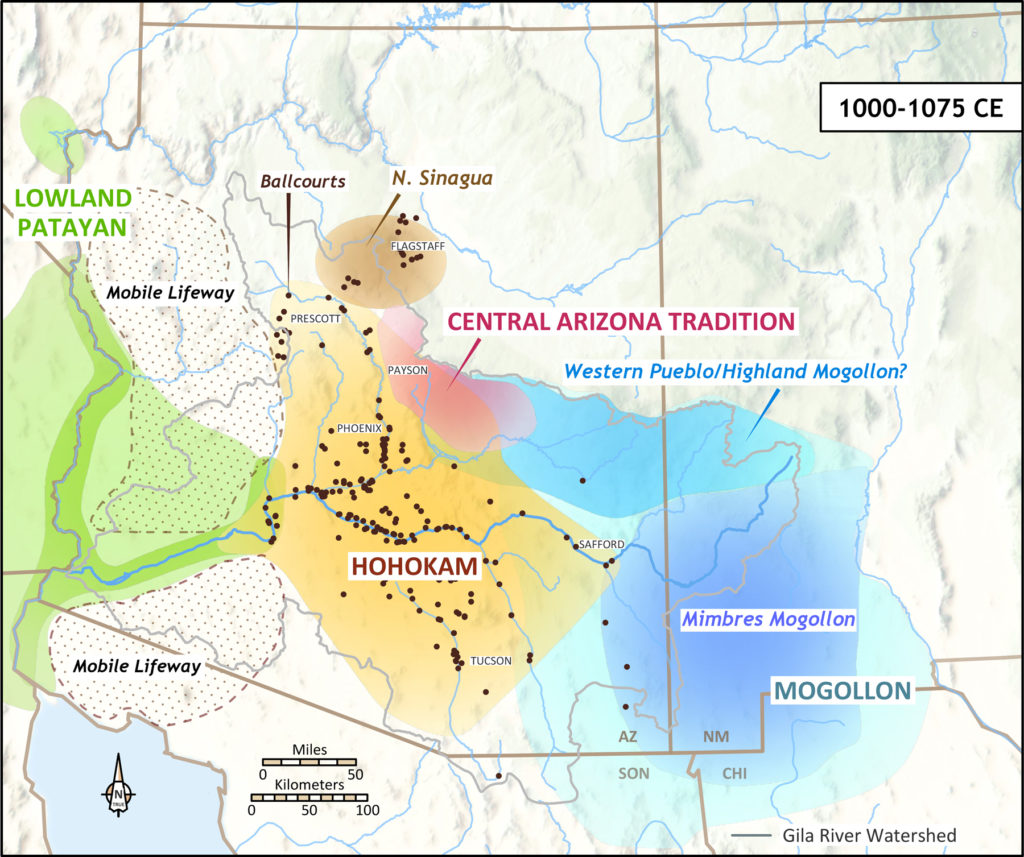

(February 28, 2020)—When contemporary O’odham talk about their ancestors, they use the term Huhugam. This is an important distinction between actual people (the ancestors) and the archaeological culture I’ll describe here. Hohokam is not really “a group of people,” but a suite of material traits found in southern Arizona that archaeologists date from 500 to 1450 CE.

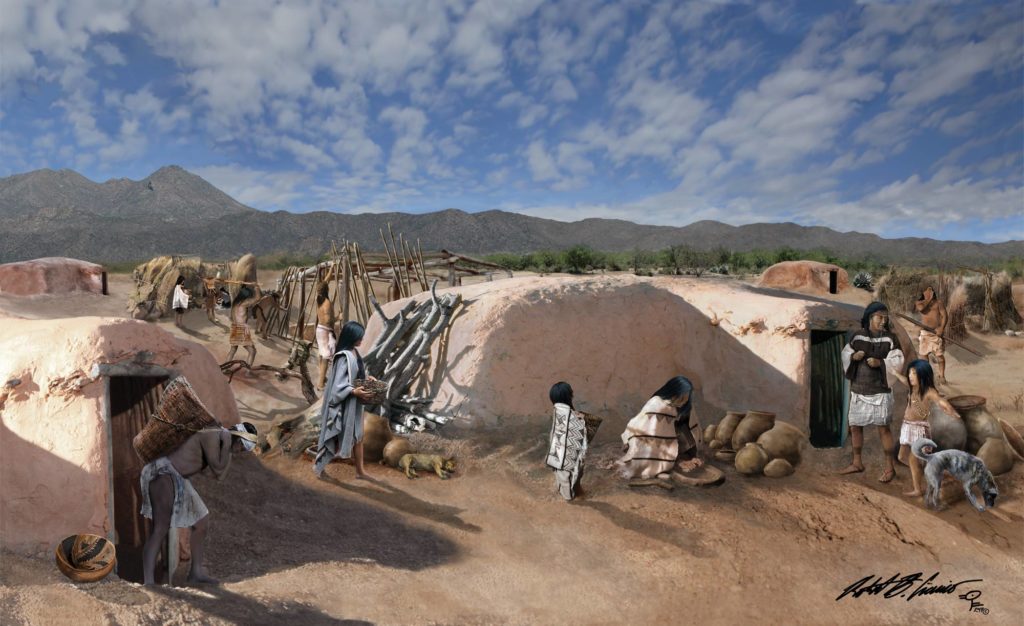

The set of traits that archaeologists (mostly) agree defines the Hohokam archaeological culture includes red-on-buff and red-on-brown decorated pottery, shell jewelry (especially Glycymeris bracelets), stone palettes and censers, plaza-oriented villages, and elaborate irrigation systems. During most of the later pre-Classic period (750–1150), people cremated their deceased, built semi-subterranean houses (house-in-pit architecture), made anthropomorphic (human) figurines, and used ballcourts as public architecture. During much of the Hohokam Classic period (1150–1450), people increasingly buried their deceased (inhumation), built their houses above the ground surface in walled compounds, made zoomorphic (animal) figurines, and built platform mounds as public architecture.

What accounts for that change? What did it mean for the people who were living in the Hohokam World and how they thought about themselves as a group?

The ancient people who lived in southern Arizona had more group identities than we will ever be able to recognize in the archaeological record. But that shouldn’t stop us from trying. Recognizing that there is variation within groups and understanding some of the mechanisms of cultural influence have direct applications to how we interact with people today.

The Hohokam Ballcourt World

Archaeologists associate ballcourts with a widespread ideology that was probably an important aspect of a large-scale group identity during the pre-Classic period. This Hohokam Ballcourt World originated in the Phoenix Basin and spread rapidly outward, especially to the south and east—to Tucson, Safford, San Pedro, and even the San Simon valley.

This ideology is identifiable in the archaeological record in the materials I mentioned above: buff or brown pottery with red-painted decoration; formal secondary cremation burials (people cremated their deceased and then spread the ashes and buried the remains); ornate stone censers or bowls and palettes; distinctive projectile point styles (dart and arrow points); marine shell bracelets and armlets; and, of course, ballcourts. These are all visible expressions of identity that would have signaled a person’s membership in the group to outsiders and insiders.

Ballcourts may be found at most of the large villages throughout the region, which works out to one about every three miles in the heavily populated areas. People watching or participating in the ballgame probably came together from several different villages, perhaps even playing against one another. That provided opportunities for visiting and for exchanging commodities in the form of raw materials and finished goods. Dave Abbott, a professor at Arizona State University, has described a marketplace system associated with ballcourts (see Rob Ciaccio’s visualization of this toward the end of Jeff Clark’s post earlier in this blog series). This idea makes a lot of sense, as people would have known the marketplace/ballgame schedule, and by extension would have known where to go to get new pots, some cotton, an axe, or whatever else they might need.

Most ballcourts are found in the Hohokam metropolitan areas, but there were also ballcourt communities in other places, beyond the major population centers, where there is considerable variability in the places, things, and material choices people made. People could use irrigation agriculture (one of the big “defining” Hohokam characteristics) in places such as Queen Creek or the San Pedro River valley, but there are also ballcourt communities in places where people couldn’t have practiced agriculture in the same ways as in the major population centers—places such as the foothills of the Superstition Mountains and the Black Hills.

In these “rural settings,” people made villages along washes that are, and were, by no means perennial and could not have supported irrigation networks. One pattern I’ve noticed at sites in rural areas is that they have very little decorated pottery, whereas sites in the main population areas have abundant decorated pottery. That means sites in those areas are missing two of the major archaeologically defined Hohokam traits—irrigation and decorated pottery. I think that has some really interesting implications for the diversity of group identities within the wider umbrella of “Hohokam” that might map on to specific valleys and basins, as well as other, more localized regions.

Those smaller, more localized group identities are expressed in subtler ways that reflect how people learned basic tasks, gaining knowledge from family members and other respected community members over time. We can see these subtle, low-visibility expressions of identity in people’s choices about ceramic temper (materials potters added to their clays to enhance technological attributes), the specific interior features of their dwellings, and what sources of materials they preferred for making tools.

A Time of Transition

These are also aspects of group identity that are more resilient and more likely to survive large-scale changes, such as the reorganization we see during the pre-Classic to Classic period transition—a time when people stopped using ballcourts (sometime around 1080) and most of the visible signifiers of ascribing to that ballcourt ideology, but before the time when a new ideology associated with platform mounds was on the rise (after 1200).

During this time of social flux, the larger, overarching group identity faded rapidly, but the smaller-scale, local identities persisted. People began making all of their pots locally. Pottery designs, which had been consistent across the whole region in the Hohokam Ballcourt World started to vary; and public architecture was different in different places.

Then, within a generation or two, a new sociopolitical religious movement (a new ideology, a new way of thinking) took hold—what we see archaeologically as the Hohokam Platform Mound World.

The Hohokam Platform Mound World

Like the ideology associated with the Hohokam Ballcourt World, this ideology probably emerged in the Phoenix Basin and spread to the south and east from there. Unlike the Ballcourt World, however, the Hohokam Platform Mound World was more hierarchical and less cohesive. Fewer new things appear in the archaeological record with platform mounds than is the case with the appearance of ballcourts—there were fewer visibly important items, and these were used by a narrower set of people.

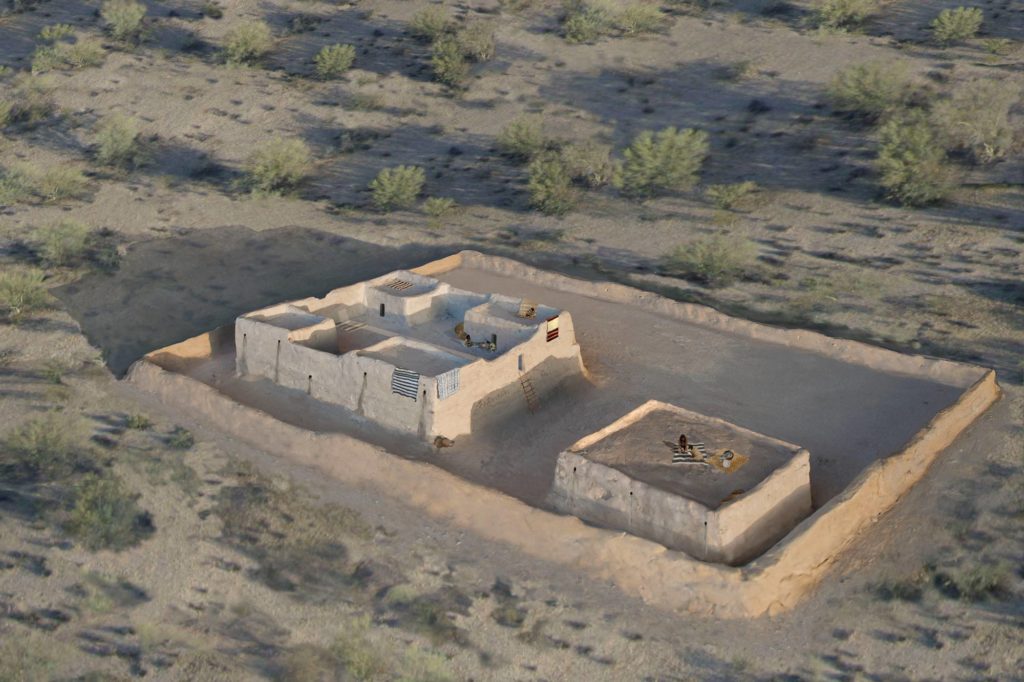

Visible markers of identity in the Platform Mound World include people’s use of inhumation burial (although not exclusively), walled compound architecture, zoomorphic (animal) figurines, and—of course—public architecture in the form of built platform mounds. Sometimes, platform mounds were large, massive-walled structures with interior “cells” and many rooms on top, but in other cases, they were much smaller. Those smaller mounds possibly reflected communities showing that they meant to be part of this world.

Archaeologists still argue about the function of platform mounds. Did people live on them? Did their purpose change over time? Most of us agree, though, that platform mounds were involved with ceremony. The ideology associated with platform mounds was probably less inclusive than the one associated with ballcourts, by nature of who was allowed to participate and the more restricted access to the ceremonial areas. Still, most villages of the era had at least one mound to show participation in the larger group identity and its ideology.

Over the course of a millennium, large-scale Hohokam group identities ebbed and flowed at a broad landscape scale. But at the local level—at the scale of the village, valley, or basin—identity was probably much more persistent over time.

One thought on “Life of the Gila: Hohokam Worlds”

Comments are closed.

Did masonry architecture begin in the early Soho phase or was it much later about the time of the earliest Salado polychromes in the Phoenix area?