- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Reporting Archaeology: Lost and Found (UPDATE)

Dr. Christopher Fisher, one of the researchers involved with the project Mr. Castillo discussed in his guest post of March 17, 2015, contacted us with comments. First, we share Dr. Fisher’s comments, followed by Mr. Castillo’s response. Mr. Castillo’s original post follows these updates.

Christopher Fisher’s comments (April 17, 2015):

As one of the archaeologists involved in the project discussed in the post I was disappointed to see that [the recent blog post, “Reporting Archaeology: Lost and Found”] perpetrates many of the errors and untruths that have appeared in social and print media. To this end we have prepared a FAQ to help interested people and the media separate fact from fiction in regard to our project.

http://resilientworld.com/2015/03/18/media-faq-for-the-utl-mosquitia-honduras-project-2015/

Specifically in regard to the blog article I wish to clarify the following items:

“highlighted the flippancy of the team in taking literally the mythical story of the White City”

At no time in any print or media venue has any member of the team declared that any of the settlements that we have been able to document correspond to the place known in Honduran oral tradition as “La Ciudad Blanca” or that has been popularized outside of Honduras as the “Lost City of the Monkey God.” The news article on the National Geographic magazine website made the point: there are many lost cities. However, the importance of this place called “Casa Blanca” as part of the intangible national heritage of Honduras, and particularly of the indigenous peoples of La Mosquitia, has never been negated.

“the lack of professional Honduran archaeologists on the exploring team”

The 2015 field team consisted of seven scientists including two Honduran researchers in lead roles on the project. Oscar Neil Cruz, who is the lead archaeologist for IHAH and who has worked in the Mosquitia region, collaborated with the team throughout the duration of the project and participated in the ground verification efforts and the archaeological interpretation of ancient settlements. Juan Carlos Fernández-Díaz is a LiDAR researcher with NCALM and the University of Houston. Dr. Fernandez has played an important role in the project from the initial LiDAR acquisition in 2012 to the ground verification efforts of 2015.

“such important news for Honduran archaeology was first published outside Honduras”

The news blog piece was first posted on the web at the request of the Honduran President and the current Director of the Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia (IHAH) after a formal announcement had been made by President Hernández at a Press Conference in Honduras. A letter to that effect from Virgilio Paredes Trapero, current director of IHAH, is posted after the media FAQ linked above.

“how the recent work in the Mosquitia and its reporting overlooked the long history of scientific archaeological research in the area, giving the impression to the general public that the region was just newly spotted”

In our scholarly work dealing with the Mosquitia region, we applaud and recognize the contributions of previous researchers, both local and foreign. Since 2012, this includes two peer-reviewed academic publications and papers presented at four academic conferences in the United States, Honduras, and Europe. All of this work includes extensive bibliographies with scholarly citations as vetted by the peer-review process. It should be recognized that the short news announcement by Douglas Preston posted on the National Geographic magazine website on March 2nd is not an academic piece, and as such does not include citations. In his longer 2013 New Yorker article on the project in May of 2012, to which the news piece visibly linked, Preston included significant sections on previous work, along with interviews with many scholars engaged in research within Honduras.

Two separate threads also appear in the article that are untrue. First, that we did not connect our findings with modern groups in the area, and that we did not contact or work with local indigenous groups.

The specific area investigated is a pristine tropical wilderness with no evidence of modern human settlement, roads, agriculture, pathways, or other presence. This doesn’t rule out the possibility that indigenous hunters have occasionally accessed the area, but no clear evidence of their presence was noted by the research team. Botanists who were part of the team concur with these findings. This is also consistent with the 2012 LiDAR results which clearly show no human-generated clearing, deforestation, or other intrusion. To be able to tread lightly in this tropical wilderness was a privilege that has been acknowledged by every member of the team.

By contrast, the team’s ethnographer, Dr. Alicia M. González, met with members of local indigenous Miskito and Pech communities. The overwhelming concern voiced was about the impact of deforestation on their lives, especially those whose livelihoods are dependent on the rivers: “Se están secando los ríos porque cortan los arboles y se van los animales porque no tienen comida, y hay menos pescado.” (“The rivers are drying. They cut the trees and the animals leave because there is no food and there are less fish.) Dr. González also worked with several Honduran special forces soldiers who are Pech, Miskito, Garifuna and Tawahka, who were being trained to safeguard the Biosphere. The valley we investigated is approximately 75 kilometers from the nearest indigenous Pech village.

The second thread touches on the impact of this recent work and the media attention will play in cultural and ecological conservation.

The Mosquitia Biosphere is clearly endangered. From 1990 to 2005 37.1% of Honduran forest cover was destroyed due to illegal logging and deforestation – largely for beef production. In 2011 the reserve was placed on the UN danger list at the request of the Government of Honduras as a result of “Illegal settlement by squatters, illegal commercial fishing, illegal logging, poaching and a proposed dam construction.” In the two years since our three areas of investigation were documented using LiDAR, illegal clearing and deforestation has approached within 12 miles of one valley, and has decimated the floor of a second. Ancient settlements now visible in recently cleared areas of the biosphere are presently undergoing looting and damage. Undoubtedly something must be done to stem the tide of this loss.

After the announcement of the initial LiDAR findings in 2012 former president Porfirio “Pepe” Lobo Sosa created an archaeological preserve to help protect the cultural patrimony of the region. On 03/10/15 President Juan Orlando Hernández Alvarado announced that the Honduran Military will set up a formal protection zone around critical areas of the Mosquitia preserve to initiate efforts to stop deforestation. Additionally, Honduran officials will begin a program to reclaim some areas lost to deforestation. This includes protections around the zone visited in 2015 along with other archaeological sites known to be in the region. Virgilio Paredes Trapero, current director of IHAH, has stated that international resources are necessary to further protect the extended Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve in which the valley we investigated in 2015 is embedded.

Recognition of this official call for assistance is signaled by a formal statement from the United States Senate floor made by Senator Patrick Leahy from Vermont that included the following:

“President Hernandez’s commitment to preserve these archeological sites from looters and other criminal activity, and to protect the broader forest area by replanting the jungle and countering deforestation, deserves our support. I look forward to working with the Government of Honduras on how the United States may be able to assist its conservation efforts.”

These announcements signal official Honduran Governmental and International recognition that the Mosquitia is endangered and a new willingness to engage in efforts at preserving the important ecological and cultural patrimony of the region.

Christopher T. Fisher, Ph.D.

Archaeologist, Associate Professor, Anthropology, Colorado State University Graduate Degree Program in Ecology, Institute for Society, Landscape, and Ecosystem Change

Victor Castillo’s response (April 26, 2015):

I appreciate Dr. Fisher’s comments on some of the points that mass media coverage has obscured regarding the recent findings in Honduras. Since his clarifications specifically concern the summary of criticisms made elsewhere by experts in the area, here, I intend to focus on my own claims in case they require further clarification.

My point is to highlight how sensationalized news coverage distorts the impact of archaeological research. A closer look at my arguments will find that what I am criticizing is the way in which sensationalized archaeological reporting nurtures the demand for specific story lines form the public and how this sensationalization becomes entrenched in the practice of archaeology in Central American countries, perpetuating stereotypes on archaeologists’ work.

I want to illustrate my claims with an update on the search of the White City. Although National Geographic’s reporting on the findings in Honduras stated that the team who discovered this “lost city” does not believe in the existence of the White City (something that I also acknowledge in my post), what was reported elsewhere was, in fact, the finding of this legendary place. This contradiction is worthy of attention. Central American press just reported a few days ago that the Honduran Government and National Geographic have come to an agreement to study the White City (press releases in Spanish can be found here, here, and here among several others).

Note that the finding of the White City is uncontested in these reports; the White City has finally materialized and its finding has become engrained in popular conscience. The relationships among archaeological reporting, the practice of archaeology in Central America, and the demand of story lines from the public is exemplified here rather clearly.

Above all, my intention on the previous post was to call attention to how, seemingly, the only way in which archaeological research makes it into the news is by perpetuating the trope of discovery in presenting archaeological findings in terms of “lost” and “found.” I find problematic the concept of “lostness” that seems to be key in the development of the recent findings in Honduras. This notion does not only refer to the probable presence or absence of indigenous population in the area, but it is connected in a more abstract manner to the epistemology of narratives of a distant past and the appropriation of real or mythological places by native groups and, in a larger scale, by a Central American nation.

As a Central American archaeologist, I see the emphasis on the “lostness” imposed onto our archaeological heritage as a very worrisome practice, particularly in regards to the incipient efforts of Central American countries in building university-level schools of archaeology and for promoting the leadership of local archaeologists in Central American archaeology. I hope that forthcoming peer-reviewed publications will clarify the concerns that the general public and academics may have about these recent findings. I also hope that Central American scientists can take part in assessing and validating the results.

ORIGINAL POST (March 17, 2015):

Over the past few days, news all over the world has been reporting the alleged discovery of a “lost city” in the jungle of the Mosquitia in eastern Honduras. According to the original reporting from National Geographic, members of an expedition surveyed and mapped several earthworks, plazas, and mounds, and they located stone sculptures and other unique features, all supposedly representatives of a “vanished” culture. Although headlines highlighted the finding of the lost and legendary White City, a mythological ruined place supposedly hidden in the Honduran jungles, the reporting argues that archaeologists no longer believe in the existence of a single lost city in the area, because this region apparently conceals several such lost places. This, according to the reporting, suggests something even more thrilling—the existence of a “lost civilization.”

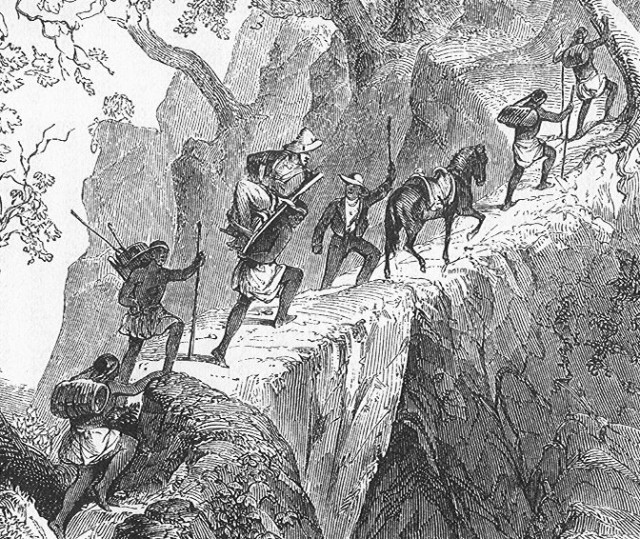

The White City of Honduras has captured the imaginations of explorers and adventurers for a long time. Claims of its existence have been traced to a vague reference to a lost city in Honduras that was mentioned to Hernan Cortés at the time of his visit to the area in 1526, and that has been merged with later oral traditions and reports of sights of lost cities. During the 1940s, an American explorer claimed he had found it, although he never revealed its precise location. In fact, the news that just broke over the past few days is the last wave of a series of announcements arguing that, indeed, the White City does exist and it has been documented, although its precise location is still kept from the general public (a comprehensive narrative on the search for the White City through time can be found here).

Back in 2012, news of the discovery of the White City came from the highest levels of the Honduran government. Using LIDAR, a remote sensing technology that allows to researchers to scan and survey a spot from the air using lasers, members of the same exploring team that reported the find days ago detected the existence of human works on the ground under the dense canopy of the Honduran jungle. When the first reports of the alleged finding of the White City spread in 2012, indigenous Honduran archaeologists and experts sounded the alarm that all these “discoveries” were being made outside the standards of scientific archaeological research. Indeed, not a single Honduran archaeologist was part of the team that reported the supposed find of the White City in 2012. Following this thread, the latest reports of the physical inspection of the ruins of a lost city by the exploring team—or even the finding of an entirely unknown civilization—are the last events of the saga in the hunt of the legendary White City of Honduras.

When the news about the recent “discoveries” in Honduras spread a few days ago, Honduran and American archaeologists quickly and strongly contested the reporting. Criticism from Honduran archaeologists highlighted the flippancy of the team in taking literally the mythical story of the White City, the lack of professional Honduran archaeologists on the exploring team, and their dismay that such important news for Honduran archaeology was first published outside Honduras. Rosemary Joyce, a renowned American archaeologist and specialist in Honduran archaeology, stressed in her blog how the recent work in the Mosquitia and its reporting overlooked the long history of scientific archaeological research in the area, giving the impression to the general public that the region was just newly spotted. In essence, many of the critics dismissed the news of the find of the White City and a lost civilization as a lot of hype.

![Map by Cacahuate, with amendments by Joelf (Own work based on the blank world map) [CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Map_of_Central_America-640x457.png)

Although Central American governments and local universities fund some archaeological projects in the area, most of the archaeological research is conducted by foreign archaeologists, who are usually funded by foreign universities, private foundations, and foreign state agencies. For most local Central American archaeologists, the only way to secure a job and make a career in archaeology is through engagement and collaboration with these foreign projects. This is, in the vast majority of the cases, a good thing. Central American researchers and foreign archaeologists benefit from each other at different levels. Local archaeologists get training in new technologies and theoretical frameworks not available in Central American countries, and foreign researchers learn how to deal with local politics and gain field experience working side by side with archaeologists, students, and local workers. Some foreign universities—mostly American—have offered Central American archaeologists the opportunity to pursue graduate studies abroad, creating scholarly and professional networks that transcend political and geographic boundaries.

But Central American archaeologists feel worried and disappointed about the publication of romanticized stories about the archaeology of the region because, in most cases, those story lines completely dissociate the region’s past from modern groups and from the actual professional practice of archaeology by native-born archaeologists. Sensationalized archaeological reporting fabricates a romantic and idealized image of the past and its remains, which are portrayed as objects in the jungle latently awaiting their intrepid foreign discoverers.

This has to do, of course, with the idealized image that the public worldwide holds about archaeologists and their work. Reporting about lost civilizations and lost cities tends to strengthen the popular notion that the work of the archaeologist is to find exceptional remains of the past. Accordingly, the idea that archaeologists are adventurous explorers or collectors of exotic objects is further ingrained in popular consciousness, profiling archaeological research in a decidedly stereotypical manner. Regarding the recent finds in Honduras, Ricardo Agurcia, a renowned Honduran archaeologist, stated to the Honduran newspaper La Prensa that he sees the claims of finding the White City as something with “a lot of tinges of adventure, of Hollywood films, as if it were from an Indiana Jones movie.”

Spanish archaeologist Álvaro Carvajal Castro and his colleagues have coined the epithet “the Indiana Jones syndrome” to address the complex set of valuations and expectations that modern societies put on archaeologists’ work, which are modeled mainly by the media (particularly the film industry) and archaeological news coverage. In this sense, what media reports about archaeological finds shapes a certain demand from the public, which in turn embraces specific narratives about discoveries and lost worlds; then, it becomes a vicious cycle in which the supply and demand of specific news story lines gets out of the control (or even the input) of the archaeologist.

![Media and news coverage perpetuate myths about archaeologists among the public, which means that the public only engages with archaeological reporting that reflects those myths. Illustration by Gary Stewart, Gary2880 (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Figure-3-1.jpg)

The connection of modern groups with the archaeological past is of vital importance in Central American archaeology, and notions of “lost civilizations” deprive descendant groups from the historical connections that they hold with ancient societies. Christopher Begley—an American archaeologist who is an expert in the Mosquitia, having conducted his doctoral research in the area and undertaken extensive field work in eastern Honduras for more than two decades—has explained how the White City is a figure present in the mythological narratives of the indigenous communities of the Pach and the Tawahka. Those groups conceive the place not as a lost ancient city, but as a hidden place where gods and ancestors sought refuge. In a sense, the White City should remain always out of sight, never to be found, because it is a complex allegory of the historical experience of these indigenous groups.

Thus, instead of taking for granted the historicity of legendary places and engaging in a hunt to discover them, “explorers” should start their work by asking how these narratives of a distant past are relevant to modern groups. They should consider how information derived from those narratives are significant for understanding the ancient societies that populated Central America in pre-Hispanic times and whose descendants still inhabit the region.

In a recent open letter, several prominent international scholars (including Honduran archaeologists) voiced their concerns about the impact this reporting of the recent finds in Honduras may have on the practice of archaeology in the area. Among other points, the scholars argue that because the reporting presents the idea of an exotic past for the Mosquitia, the knowledge of the modern indigenous populations living in the area is ignored—and, ultimately, disrespected. Then, this flawed and failed reporting of fieldwork perpetuates the discourse in which only the “discoveries” made by a certain stereotyped explorer become relevant for the public, even though what is been “discovered” has been known by locals for generations.

The recent archaeological reporting on the “discovery” of the White City is just one example of the conundrum in which the practice of archaeology in Central America is entrenched: successful international collaboration and mutual enrichment between local communities and local and foreign archaeologists are obscured and devalued by reporting about “discoveries” that reduces research on a region’s history to “lost” and “found.” Surely, the peoples who lived in the past and their modern descendants deserve something better.

Editor’s note: Mr. Castillo is a Guatemalan citizen and a Ph.D. student in the School of Anthropology, University of Arizona.

One thought on “Reporting Archaeology: Lost and Found (UPDATE)”

Comments are closed.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.

Dr. Fisher seems to have missed the point of the original article despite its title: “Reporting Archaeology: Lost and Found.” As a colleague of Castillo’s, I may be biased, but I appreciated Castillo’s thoughtful analysis of the state of Central American archaeology and how it relates to archaeological reporting to the public. For me, Fisher’s reply actually illustrates Castillo’s conclusion that “successful international collaboration and mutual enrichment between local communities and local and foreign archaeologists are obscured and devalued by reporting about ‘discoveries’ that reduces research on a region’s history to ‘lost’ and ‘found.'” It is wonderful to read that Fisher’s and colleagues’ archaeological research may contribute to the preservation of the Honduran rainforest. However, I think we should ask why an Indiana Jones-style public narrative is necessary to spark interest in the conservation of cultural and natural resources, and we should reflect on the incongruousness of such an adventurer/tomb-raider mentality with the protection of cultural heritage and the prevention of looting. It is a complex situation, and there is much to think about here.