- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- Creepytings versus Rock Art and Banksy, Part 2

Read this first part of this post here.

View examples of Creepytings’s graffiti at www.modernhiker.com.

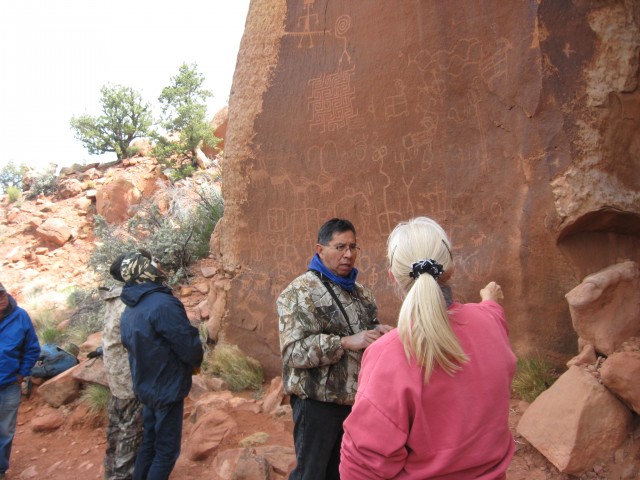

The second argument that bloggers and commentators have rolled out to defend Creepytings’s actions is that we shouldn’t view her work any differently from the rock art that is speckled across much of the American West. But here, too, we have a major difference in meaning. We know that much of that rock art was created for specific purposes. Some to mark territory, some to record specific events (such as astronomic explosions, volcanic eruptions, spiritual visions, and migrations), some astronomic record keeping, and some interactions with other groups. Rock art was a very real way for people in the past to interact with each other through time—even if it was only a week apart—and to create a permanent system of observation.

Yep, that’s right. Some rock art records empirical observations. Some rock art isn’t even technically art, it’s science!

Of course, we’ll never truly know why all rock art was created. That’s not how history works. Whether it is text-based evidence, artifacts, or art, researchers interested in the past will always be reexamining current models as new data become apparent, new misunderstandings are revealed, and data are looked at in previously unthought-of ways. Although we always strive to get a more accurate understanding of the past, we’ll never get a perfect one.

Many existing rock art sites are still visited by modern tribal groups. They are sacred sites now. Places with stories, meanings, history, and observations about long-gone human activity. Places of reverence. Sacred terrain. So, no, Creepytings’s drawings don’t equate well with any of the uses or meanings attached to Native American rock art. That’s my opinion as an anthropologist, at least.

I casually asked friends and acquaintances of mine in the art community whether they considered this to be art or not, and to explain. Here’s what they have to say:

Rob (artist): “I don’t like it and I consider it vandalism. These are sacred places for some and national nature lands should be ‘leave no trace.’ I remember backpacking in the Big Horn Mountains as a kid and hiking far in and seeing garbage in the stream. What she is doing is pretty much the same thing to me. There are plenty of other forms of media to display your art and few places of untouched nature. Saying this, I do like street art and graffiti, but its place is in the city.”

Sarah Anne Stolte (art historian): “Whether or not the Creepytings drawings should be considered ‘art’ is like asking the highly debatable, arguably unanswerable question, “What is art?”. Although I would consider Creepytings to be graffiti style art works, intended as such by the maker and exhibiting certain aesthetic properties, I also consider these art works to have been created with ill-guided intentions and with a problematic choice of medium in tandem with the selected canvas. They are, thus, both art and vandalism.

“Graffiti intended by the maker to be ‘art’ and that adheres to certain aesthetic criteria including, but not limited to design, composition, and meaning, can be, in my opinion, considered art. The fact that graffiti is usually illegal and often defacing of public structures is inherent to the practice. I will not comment on whether I think the practice is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ as it is, I believe, a separate issue. These particular works were generated with the intent of being art that evidences the artist’s presence on specific landscapes. The forms and compositions are well-designed. Is it art? Sure. Is it good art? Well, that is an entirely different question. From my perspective as an art historian, the issue with Creepytings is not so much a question of ‘is it or is it not art’ as much as it is an illustration of how contemporary Americans consider their relationships to the environment, the history of the American landscape, and the continuity of Native American cultures.

“I think it is without question that this particular artist made several substandard art practice decisions. National Parks are sacred places created with the intent of preserving and protecting the natural environment from what is often visualized as modernism’s impending and ever-encroaching destructive effects on the planet. Would the discussion be different if the artist had chosen to use natural pigments rather than acrylic paints as she marked her presence on the land? My mind recalls, for example, Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty of 1970, and although this is perhaps not the best comparison, it does offer room for thinking about how contemporary Earthworks and graffiti converge and diverge.

“An example of a more thoroughly conceptualized graffiti-style art practice is evidenced in the work Ryan O’Malley. Made of materials that will decompose naturally and not cause any harm to the environment, O’Malley corn-pasted his prints on the streets of Venice, Italy during the exhibition, “Epicentro: ReTracing the Plains”.

“To those adamantly commenting that the Creepytings artist defaced the natural environment and should be criminally punished as a vandal, I ask why they extend their protection of the planet only to National Park spaces and urge them to consider their own, daily footprints on the environment. I bet many of these angered citizens unconsciously pollute the air, water, and land each day through driving and other daily consumption practices.”

Peter Janus (artist): “Some artists will do anything to get their names out there. No matter the cost sometimes. There are tasteful ways of doing this, but in this case, it’s just low class. National parks are there for the beauty of nature, not this. I am concerned that if this getting attention, what others might attempt.”

G. Bearskin (artist): “As an artist and Native American Indian, the law is the law. And she cannot compare her work as the same as rock art, otherwise “most of” the ancients’ symbols would not be unexplained. Charge her.”

Anonymous female (art historian): “There might be two camps from an art historical perspective on this woman’s tagging and behavior. The first might side with graffiti practice and the perceived artistic ‘right’ to tag public spaces (à la Banksy, who has gotten so much press recently and has a large following via social media). Tags and graffiti images mark/change a landscape (not only the physical) and in some cases make political or social statements that spark discussion and critical thinking, like all good art should do. On the other hand, the spaces in which she has decided to tag have a long history, both in terms of the age of the earth, and also the use by the native peoples of this country. Ultimately, the land was set aside for the enjoyment of all the people, and therefore one person’s permanent changes to that landscape go against the democratic intent of the parks and the landscapes within them. Also, I am suspicious of this woman’s choice to also tag a bathroom. If there was a strong artistic impulse that perhaps honored or mimicked indigenous rock art (and equally respected the spaces where those images are typically found), I might be more willing to say ‘okay, she’s attempting something here, albeit badly.’”

Niel (artist, tattoo artist, former gallery owner): “Short answer: Vandalism.”

Anonymous male (art historian): “I really lament these actions on the National Parks. For me, it is obviously a wretched way of pursuing media exposure. The way this person is trying to bring attention to her actions does not dignify anybody, least of all herself.

“A lot of people pursue attention by performing gestures that are upsetting to people, or controversial, in order to get their names out there and from that platform of discussion launch themselves as ‘artists’ and commercialize stuff through the newly minted name they think they are acquiring. I am not impressed by any of the drawings, much less by the gesture of making unsophisticated marks on what belongs to everybody, namely the national heritage.

“There are many reasons why this would not qualify as art, perhaps mainly for its betrayal of social institutions, yet more pressing is the question, would this even qualify as graffiti? The answer would depend on what is being transgressed. Graffiti being a rather urban phenomenon, this person’s gestures are cast into a dubious sphere. I recommend discussing this ambiguity with someone in a better grasp of notions of graffiti and the whole legality and institutionality regarding the park.”

6 thoughts on “Creepytings versus Rock Art and Banksy, Part 2”

Comments are closed.

I am not sure asking if the work done by the woman under the name Creepytings is “art’ is relevant. What it is, is destructive, culturally imperialistic, self absorbed vandalism. There is no way her acts can be compared to prehistoric rock art, just because the base medium is the same. The values, message, intent and design of Creepytings work, those of destroying natural beauty, destroying sacredness, destroying solitude and elevating “self” as the focal point of nature, on lands that were set aside based specifically due to these qualities, is more than merely profane. It is arrogant, conceited, self absorbed self promotion in the worse possible manner. Had she selected a different venue of expression, say a 12th century cathedral in France, the wall of a temple in Ankar Watt, a pyramid in Egypt or Mexico, perhaps some of us could see this act more clearly for what it is. For me, what she has done is clear, and I really don’t care if it is considered art. It destroys what transcends the western concept of art.

Hi Mark,

I agree with everything that you are writing so passionately about and much of the first part of the blog (https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/2014/11/01/creepytings-versus-rock-art-and-banksy/) was my attempt to highlight those same issues. Culturally imperialistic. You nailed it. That’s exactly what I think her acts are.

The reason I chose to write this blog around whether her work is the same as street art or rock art was to address problems with what I was seeing in the national dialogue. This dialogue has been split between two camps, those attacking her deeds and those defending. Among those defending, it’s a split between saying it’s no different than street art and it’s no different than rock art. This is the same reason I asked folks in the art community their opinion as to whether it is art and what her actions might mean. I wanted to frame her actions within that context to show exactly why it is different than those two types of art and how her actions, because of that exact difference, are instead, as you said, culturally imperialistic. Since she clearly assumes her drawings are art, and the very nature of art seems to be that meaning is embedded, it seemed right to contextualize it that way. It gives us an avenue to talk about culturally imperialistic actions whereas if we framed her actions as simply vandalism, they could be written off by some as unthinking acts not worthy of dealing with. I don’t think her actions should be written off as vandalism. I think they are highly offensive precisely because of where they were placed and the fact that she saw them as art.

I also didn’t want the general legal nature of her work and street art (i.e. both usually illegal) to confuse the complete divergence in their inherent meaning.

Thanks for kicking off the comment thread!

Hi Lewis,

I can see your point about the “art vs. vandalism” designation, but I still contend this is vandalism. To say this is art elevates her acts to the level she intended. As you say, “the very nature of art seems to be that meaning is embedded”, so one must assume Creepytings had some message she was trying to express. So this brings up a few questions. First, did she succeed in getting her message out? Second, in a broader context, if the creator of an image fails to get their message out, is it still “art”? And finally, if the act is so destructive on so many levels, so offensive, in other words, if the act itself decreases the total value of experience for those exposed to it, is it really art? I live in New York and visit the city upon occasion. I have seen some incredible street art. Interestingly enough, I can not recall seeing much, if any, I would consider defacing an object of beauty. In fact, most of it ENHANCES areas of blight or poverty. And a lot of the most beautiful pieces are done in chalk, to be washed away with the next rain. I think CONTEXT is a critically defining factor in Creepytings situation. And she is a total fail in art. Maybe I am still missing the point, if so I am sure you will continue the dialogue.

Admittedly, the Western concept of art has frayed into a more interesting tapestry that now even sometimes praises art that is also vandalism, that is, until it steps on the toes of our marble statues. And that’s right where vandalism-art becomes unacceptable: when it irrevocably damages significant, shared cultural material and meanings for the sake of inflated ego.

Her vandalism-art is definitely art. I recall in art history methods seminar a frustrated Renaissance scholar messing up some food wrappers on the conference table and asking if that was art, too? It wasn’t half bad actually, I said. Most things humans make out of available materials are art once someone has decided it is, whether the maker or not. And from reading this post & viewing the images, her message of self-aggrandizement did achieve at least one of her goals, notoriety, but not with the anonymous impunity that she expected. When she chose acrylic pigment and stone on public lands as a canvas, she didn’t think she was breaking it per se, but neither did she realize that it was a serious alteration of the contexts of that terrain for other citizens.

But the question as to if a creator fails to get *their* message out, is it still art? Of course! Brillo didn’t set out for its boxes to have anything but a functional message, but look at us now. As to if something can be art that decreases the value of experience for those encountering it, the answer is also yes. If it is deemed vandalism it will likely be sandblasted or dumpstered shortly if the property owner decides to do so. But can an art-world work also decrease the total value of experience? Consider Richard Serra’s monumental, rusted minimalist “Tilted Arc,” that used to occupy and redefine a Manhattan plaza in the 1980s until a public lawsuit banished it on usability, aesthetic, and homeland security grounds. One of these days someone will make a holographic projection of it to be activated a few times a month and who knows if Serra will spearhead the project or denounce it. We might also consider that so, so poorly thought out inflatable “christmas tree” that LA artist Paul McCarthy installed in Paris last month. Soon vandals took it onto themselves to deflate it, next they cut the support cables and finally the artist gave up. For once, I think most people are on the side of the vandals here.

I agree with a lot of the sentiments here. I can’t read Casey Nocket’s mind, but I suspect that she may have justified what she did as some sort of acceptable hybrid of rock art and Banksy-style street art.

Clearly, Creepytings is neither. The reality is that she wanted to be noticed. Now this is true of most artists — they want their work to be seen, heard, read and experienced. But in this case, it seems to be more of a desire to be noticed in a social media context.

So she succeeded there. But the cost, to us, is high. National park land, designated wilderness areas, and so forth were set aside for conservation and protection purposes — to preserve wild places in their natural state so we don’t lose those places forever. Creepytings doesn’t encroach on the wild in the way, say, a strip mine does, but it is a man-made encroachment nonetheless. It goes against the shared values most Americans have in terms of why we established national parks, wilderness areas and wildlife refuges in the first place.

Is it art? Truly, that’s based on the opinion of individuals. Does it serve a purpose? Only to Casey Nocket. For the rest of us, it’s a loss, no different than the trash I pick up on the trails, or the spray-painted graffiti I can’t remove from a rock face.