O’odham peoples of the Sonoran Desert refer to their ancestors, from time immemorial to the present, as Huhugam. Archaeologists recognize the material culture of the ancestors who lived from about A.D. 400 to 1450—which researchers call “Hohokam”—as something distinct from what came before and what followed. Still, it is important to understand that what archaeologists identify materially as “Hohokam” more likely represents an ideology—a way of thinking—that itself varied across the Hohokam landscape and across those thousand years.

Over a millennium, farmers, craftspeople, and traders established large, permanent villages in the river valleys of central and southern Arizona. Unique styles of decorated pottery, specific architectural traditions, and other shared customs distinguish these ancestral people from their neighbors.

Notably, Hohokam communities built extensive canal systems to water vast fields of corn, beans, squash, and cotton. The magnitude of these systems is best attested in the Phoenix area, where hundreds of miles of canals tapped the life-sustaining waters of the Gila and Salt Rivers.

We are beginning to see the origins of Hohokam irrigation technology among much earlier communities along the Santa Cruz River in Tucson, where maize dates back to 2200 B.C., and probably earlier. Just as the O’odham see a Huhugam continuum, archaeologists have verified that Hohokam traditions were rooted in a much deeper past in the Sonoran Desert.

Living in Villages and Communities

Initially, Hohokam dwellings were “pithouses.” People dug shallow pits and built houses in them. Wooden posts and beams formed structures that builders covered with grass and adobe. Villagers arranged their dwellings in courtyard groups, such that doorways faced each other and opened onto a common central area with shared features—storage pits, ramadas, outdoor ovens, and other facilities. In larger villages dating after about A.D. 500, families arranged their courtyard groups around a central plaza area.

At most large villages dating from A.D. 750 to 1075, people excavated large oval basins that archaeologists call “ballcourts.” The excavated earth formed raised berms around the sunken courts. These open-air facilities suggest connections, probably indirect, with Mexico. Watching or participating in ball games brought people together, and it provided opportunities to visit with friends and family and trade raw materials and finished goods.

From 1075 to 1250 was a time of great transition. Villagers changed how they were living on the landscape, and communities ceased using ballcourts, though not all at once. That cessation, and the new ritual architecture that began to appear, signal important but as yet poorly understood changes in religious, economic, and social life.

Rituals associated with raised mounds first developed in the Greater Phoenix area. By 1250, these large, solid edifices with flat surfaces were common at large villages across the Hohokam world. Ceremonies conducted on top of these “platform mounds” were visible to spectators below. The religion associated with platform mounds was probably less inclusive than that associated with ballcourts. Platform mounds fell out of use by about 1350.

Also by about 1250, most people were living in aboveground adobe dwellings. Over time, they erected adobe walls that connected their houses and enclosed adjacent courtyard areas. Archaeologists refer to these constructions as “compounds.”

Making and Using Pottery

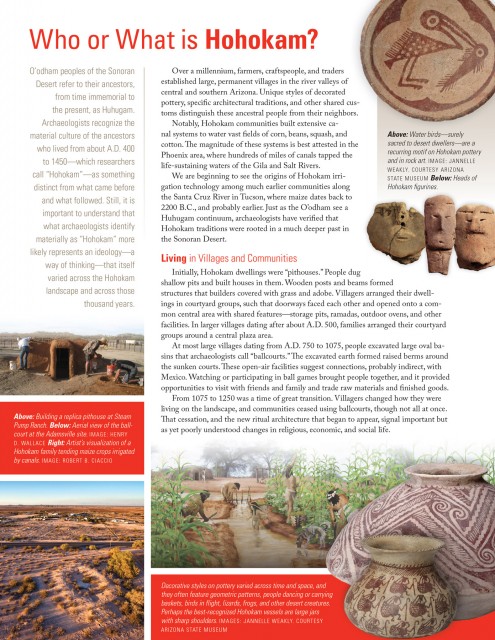

Potters of this tradition used a paddle-and-anvil technique, where they held a stone anvil inside the vessel and beat the walls with a wooden paddle to form the desired shape, size, and thickness. They had plain pots for cooking and storage and gray-, brown- and buff-colored vessels with elaborate designs in red paint. Later in time, they made polished red bowls and jars.

Making and Trading Special Things

Archaeologists associate certain objects and materials with Hohokam communities, though these were not necessarily used or made throughout the Hohokam world. These include palettes ground from reflective stone, stone censers, fired-clay figurines, conch shell trumpets, marine shell jewelry (especially armlets and bracelets), tiny turquoise mosaic tiles, cotton textiles, copper bells, pyrite mirrors, and macaws. Many of these were inspired by contemporaneous communities far to the south. Indeed, copper bells, mirrors, and macaws actually originated in ancient West Mexico and entered Hohokam communities through pilgrimage or trade.

Moving On and Living Differently

Hohokam traditions changed and seemingly disappeared, at least in a material sense, as immigrants from the northern and central Southwest arrived and the region’s population declined over many generations. A new way of thinking that incorporated local and immigrant views spread across much of the region, but not all Hohokam communities adopted this ideology, which archaeologists call “Salado.” Archaeologists do not recognize the few people still living in the area after 1450 as Hohokam, because their pottery, architecture, and way of life had changed so dramatically.

By 1500, there are so few material traces of indigenous people in the region that archaeologists infer even more drastic changes in how people were living—as mobile groups, perhaps? Still, the region’s remaining people—those ultimately encountered by Europeans such as Father Kino—are considered Huhugam, ancestors of today’s O’odham peoples.

Want to learn more? Explore the major concepts, places, cultures, and themes that Southwestern archaeologists are investigating today in our Introduction to Southwestern Archaeology.