For centuries, Native peoples of the Southwest expressed ideas through the iconography they placed on pottery, basketry, textiles, hides, murals, ornaments, their own bodies, and even the landscape itself. Using geologic features as their canvas, rock art’s creators expressed enduring visions that continue to intrigue and inspire us. In the Southwest, these visions took three forms.

People pecked, scratched, abraded, and carved petroglyphs into stone, usually by removing a dark weathered surface, or patina, to expose the lighter rock beneath.

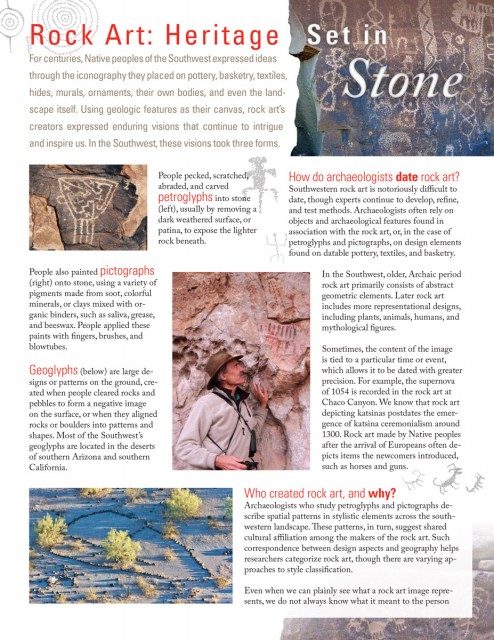

People also painted pictographs onto stone, using a variety of pigments made from soot, colorful minerals, or clays mixed with organic binders, such as saliva, grease, and beeswax. People applied these paints with fingers, brushes, and blowtubes.

Geoglyphs are large designs or patterns on the ground, created when people cleared rocks and pebbles to form a negative image on the surface, or when they aligned rocks or boulders into patterns and shapes. Most of the Southwest’s geoglyphs are located in the deserts of southern Arizona and southern California.

How do archaeologists date rock art?

Southwestern rock art is notoriously difficult to date, though experts continue to develop, refine, and test methods. Archaeologists often rely on objects and archaeological features found in association with the rock art, or, in the case of petroglyphs and pictographs, on design elements found on datable pottery, textiles, and basketry.

In the Southwest, older, Archaic period rock art primarily consists of abstract geometric elements. Later rock art includes more representational designs, including plants, animals, humans, and mythological figures.

Sometimes, the content of the image is tied to a particular time or event, which allows it to be dated with greater precision. For example, the supernova of 1054 is recorded in the rock art at Chaco Canyon. We know that rock art depicting katsinas postdates the emergence of katsina ceremonialism around 1300. Rock art made by Native peoples after the arrival of Europeans often depicts items the newcomers introduced, such as horses and guns.

Who created rock art, and why?

Archaeologists who study petroglyphs and pictographs describe spatial patterns in stylistic elements across the southwestern landscape. These patterns, in turn, suggest shared cultural affiliation among the makers of the rock art. Such correspondence between design aspects and geography helps researchers categorize rock art, though there are varying approaches to style classification.

Even when we can plainly see what a rock art image represents, we do not always know what it meant to the person who produced it. For example, a petroglyph of a deer might have symbolized what deer meant to the maker’s society, which might not be anything like what we think of when we visualize a deer. Study of rock art in its cultural and landscape context can tell us about the culture that produced it. Persistent research combining archaeological documentation and ethnographic research has shown that examination of rock art in its cultural and spatial context can offer sound and fruitful insights into the meaning and purpose of rock art.

Functional interpretations of rock art complement its aesthetic appeal. For example, panels displaying animal herds may represent a form of hunting magic. Repeated geometrics may be a calendar. Experts have shown that rock art in certain places helped track astronomical events. Some rock art may have served as territorial markers. Other functions include trail guides, maps, shrine markers, and religious imagery. Geoglyphs may have been stages for ritual practices that involved dance or motion.

Because rock art is an abiding feature on the landscape, it is in an ever-changing dialogue with the people around it—that is, regardless of the original “purpose” of an instance of rock art, modern people ascribe rock art with new or revised meaning. Campers and hunters may use an ancient rock art panel as a landmark, New Age spiritualists may use rock art for ritual purposes vastly different from what the original creators intended, and Native Americans may view ancient rock art as providing ancestral linkages to spiritual or religious practices today.

Why preserve rock art?

Rock art’s visibility is a blessing, in that it evokes our sense of wonder at the depth and breadth of human experience, and a curse, in that it can draw the wrong kind of attention. Rock art faces constant threats from vandalism, theft, development, off-road vehicular travel, pollution, and erosion.

There is far more rock art than we are able to study or conserve at present. In many ways, rock art research is just beginning. Future technological developments should enable rock art researchers to provide even greater insights into the peoples who created this amazingly diverse array of visual expression.

We need everyone’s help to preserve rock art. By helping to conserve such expressions on the places of our past, you ensure that opportunities for all of us to experience these places and learn more about that past are not lost. You honor those who came before us, their legacy on the landscape, and the ancestral and spiritual meaning these places have among the makers’ descendants.

Want to learn more? Explore the major concepts, places, cultures, and themes that Southwestern archaeologists are investigating today in our Introduction to Southwestern Archaeology.