- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- From the Field School: Cooked or Burned?

Readers, be aware that this post discusses and shows images of the cooking of packrats.

(July 28, 2025)—Coming into the field school, my mind was spinning as I tried to think of a topic for my research project. I knew I wanted to work on faunal (animal) remains, but that was about it. I was soon struck by inspiration while listening to a lecture discussing patterns of turkey consumption within ancient populations over time. By analyzing the remains of turkeys on various archaeological sites, researchers were able to identify that people consumed turkeys during a period of drought, but not at earlier times.

Learning this prompted me to question what other patterns might appear when analyzing indicators of human consumption within the faunal collections we were processing. From there, I was able to flesh out my project further, figuring exactly what type of research I wanted to do and how to do it. I have always been partial to rodents, so I decided to focus on indicators of the consumption of rodents in the NAN Ranch collections. My project then developed into a combination of in-museum analysis of the NAN Ranch faunal collection and an experimental component.

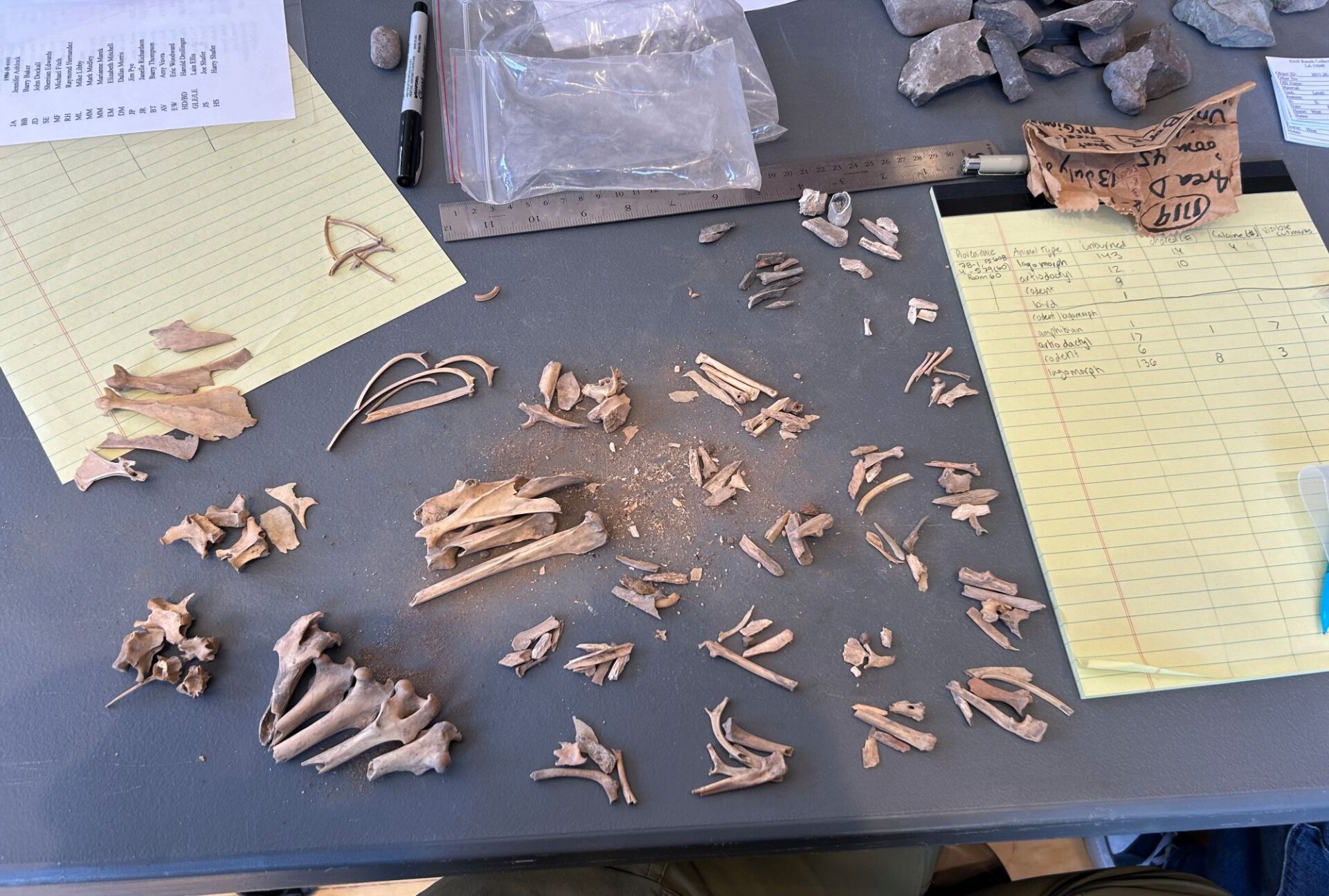

As we analyzed and rehoused the animal bones in the WNMU Museum, I recorded more detailed information on the bones. Primarily, I looked at whether the bones were burnt, recording the specific type: char or calcine. Char is when the bones have been scorched, leaving carbon residue and marking them dark or blackened. Meanwhile, calcine is the process that occurs when bones experience extreme heat, changing their appearance to be white. The presence of either on a bone offers possible evidence that the animal was cooked and eaten.

However, rodents often burrow into sites, making it difficult to know whether they arrived through natural processes or their presence is due to human actions. In the case that they are a disturbance, the burning may be due to natural fires that have occurred since the rodent’s death and can confuse the data. Because of this persistent issue, and just for the fun of it, I worked with the field school staff to develop an additional component for my project: cooking some packrats (in as close a way as Mimbres farmers might have done as possible) to create a comparison for the bones in the collection.

So, on my third day of experimental archaeology, we started a fire and placed two pack rats on the charcoal to roast. The original plan was to cook one to the point where it might be eaten, and the other we wanted to overcook, to mimic how they might look if they experienced a natural fire. After several hours (we got distracted making mud), we pulled them from the fire to examine the results. We could already tell by the burning smell that we might have slightly overcooked them (cremated them, really), but we were still able to dissect the charred remains to salvage some bones.

Excitingly, the bones we were able to extract—mainly femurs and some skull bones—were fairly consistent with those found in the collection, offering some evidence that the burned NAN Ranch bones might have been a result of consumption.

As my project developed, it certainly took some turns that I hadn’t expected. I can’t say I saw myself roasting rodents on an open fire next to a mud house when I first arrived here in Silver City, but I can say I enjoyed each step of the way. Since then, I have deepened my knowledge of faunal analysis and, more generally, archaeological research.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.