- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- From the Field School: Beneath the Beams

The History of San Estévan del Rey

(July 28, 2025)—In western New Mexico, resting on top of the towering sandstone mesa, lies the Acoma Pueblo—called “Sky City.” This ancient village is one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in the US, dating back to at least 1100 CE.

Long before the arrival of the Spaniards, the Acoma people, who once lived on the desert land below, chose to relocate and build their new home high above the cliffs. The decision to climb the mesa was driven not only by practical needs—such as protection from raiding Tribes—but also by deep spiritual beliefs. To the Acoma, living high up in the sky, they were now closer to the sun and the moon, to their deities, the rainmakers, and their ancestors. This home high in the heavens became a sacred and secluded space where their community has flourished for nearly 1,000 years.

Unfortunately, everything would change once the Spaniards came.

On our field trip with Archaeology Southwest, I had the opportunity to visit Sky City and the San Estévan del Rey mission church. Our tour guide, Gooby, provided us with a detailed account about how this massive adobe church was built 387 feet up above the surrounding valley.

San Estévan del Rey was built by the Acoma people under the orders of the Spanish Viceroy, starting in 1629. After a violent encounter with the Spaniards, known as the Acoma Massacre of 1599, the Franciscan missionaries sent Father Juan Ramirez to permanently live at the pueblo and convert and control the Acoma people.

Completed around 1641, the church stands as a stark reminder of the brutal labor and oppression forced on the Acoma people. Construction of the church demanded extensive labor, as some building materials needed to be carried from the San Mateo Mountains, some 30 miles away. These massive beams (Ponderosa pine vigas), weighing over a ton each, had to be carried down the mountain and then hauled up the cliffs and installed up on the 40-foot ceiling. To punish the Acoma people further, Father Ramirez demanded that the beams not be allowed to touch the ground, as it was sacrilege, and if they did, the punishment was death. So, the Acoma men carried them on their backs and chests, even sleeping with them to avoid execution.

Despite this suffering, the Acoma found subtle ways to resist. They painted the vigas red and white to symbolize the balance between male and female spirits and incorporated sacred symbols into the altar of the church.

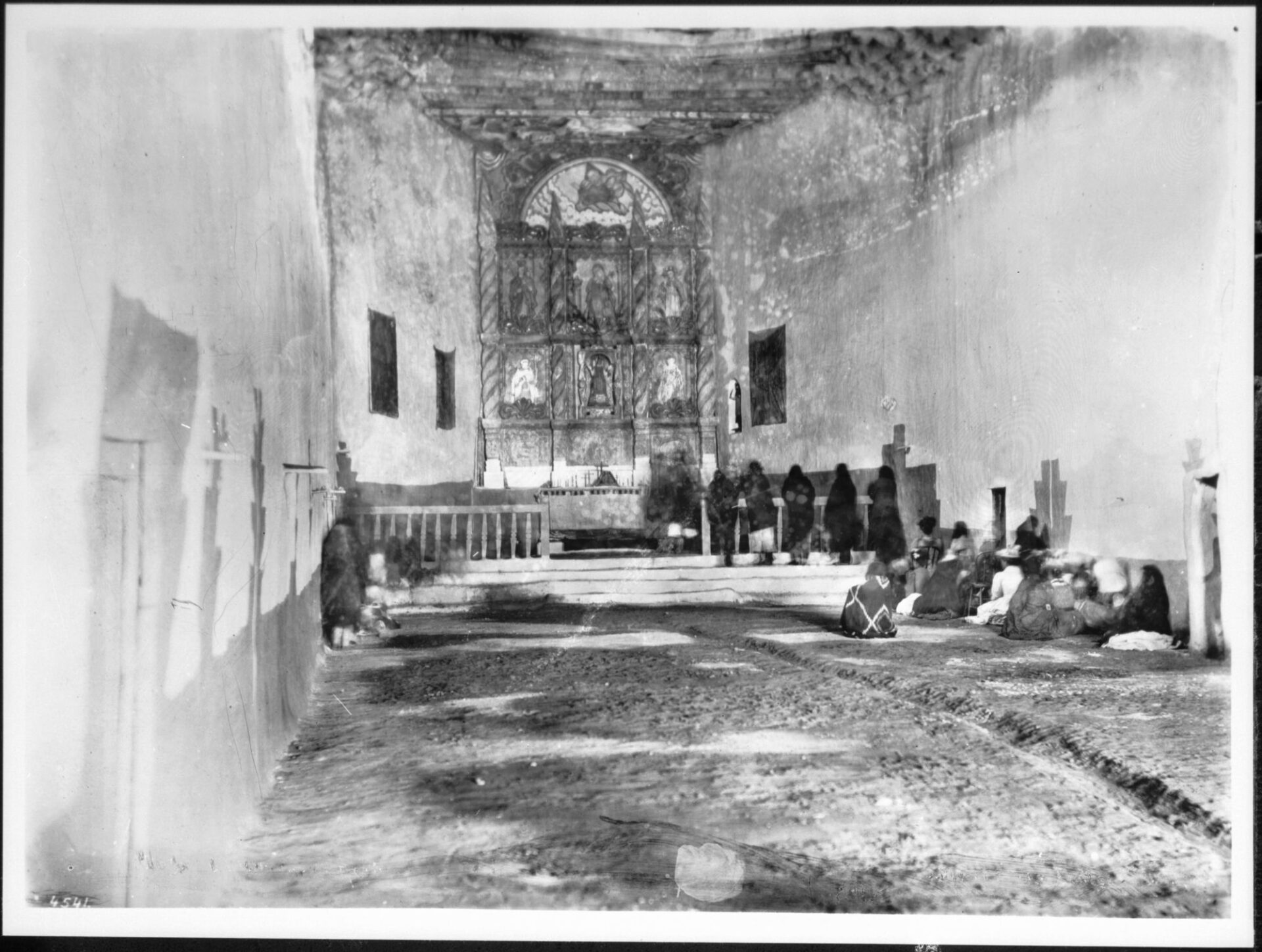

When Spanish rule finally ended, many Tribes tore down their mission churches. But the Acoma didn’t. Their church had been built directly over their sacred kivas, and tearing it down would have meant destroying their own sacred ground. Instead, they reclaimed it. They rebuilt the central altar in their own vision and painted images of rainbows, clouds, and corn—all central to Acoma tradition. Today, the church is not so much a place of daily worship as a gathering space for traditional ceremonies. Once a year, families come together to mix adobe mud and repair the church’s walls—preserving it not because of its colonial past, but because of the new meaning they created for it.

Standing inside that church, I felt the weight of forced history—the suffering, the sacrifice—but also the defiance and enduring strength of the Acoma people. San Estévan del Rey is more than a mission church. It is a living monument to Acoma resilience.

Bibliography

George Wharton James. Old San Estevan Del Rey Mission Church, 1886. Accessed July 11, 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Interior_of_the_old_church_during_early_morning_mass_at_the_Acoma_Pueblo,_New_Mexico,_1886_%28CHS-4541%29.jpg.

Kilroy-Ewbank, Lauren. “Mission Church, San Esteban del Rey, Acoma Pueblo.” Khan Academy. Accessed October 16, 2019. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/new-spain/viceroyalty-new-spain/a/acoma-pueblo.

U.S. National Park Service. “San Estevan Del Rey Mission Church – Spanish Missions/Misiones Españolas.” Accessed July 11, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/travelspanishmissions/san-estevan-del-rey-mission-church.htm.

Wikipedia contributors. “San Estévan Del Rey Mission Church.” Wikipedia. Last modified July 5, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Est%C3%A9van_del_Rey_Mission_Church.

World Monuments Fund. “San Esteban Del Rey Mission.” Accessed July 11, 2025. https://www.wmf.org/monuments/san-esteban-del-rey-mission.

Explore the News

-

Join Today

Keep up with the latest discoveries in southwestern archaeology. Join today, and receive Archaeology Southwest Magazine, among other member benefits.