- Home

- >

- Preservation Archaeology Blog

- >

- The Power of Symbols

(November 14, 2016)—As an anthropologist, I think about the power of symbols, and their power to unite or divide.

When I taught traditional classroom anthropology courses, this was one of the key concepts we discussed. As a young teaching assistant for Peggy Nelson (a professor in the Barrett Honors College at Arizona State University and an amazing teacher), I watched her use a simple exercise to get this idea across.

She asked students to name symbols and drew them on the white board. Then, she picked one seemingly at random—the AAA symbol of the American Automobile Association—and asked what and who it represented. I watched people’s expressions shift as she asked what students would think if they saw it in different locations: on a pin on someone’s shirt? Painted on a building? Set up on a grassy hill and burning on a dark night? Everyone laughed at that one.

Then she did the same thing with an American flag and a cross. On a pin or a building, they carried a set of ideas students were comfortable with. Burning? Nobody laughed.

Archaeologists spend a lot of time trying to understand aspects of what symbols meant to the people who used them in the past. In the Southwest, many of the symbols preserved in the archaeological record are in rock art or on pottery. Pottery made in the Mimbres area of southwest New Mexico is especially appealing because its naturalistic images seem to invite interpretation. Some images might depict stories; some might have been for entertainment; still others for religious instruction, parts of oral histories, or combinations of those and other roles. But all of them stood for ideas important to those who used them.

A very specific set of design rules governs how this pottery was made, and potters managed feats of creativity and expression without deviating from those rules. This shows another important characteristic of Mimbres pottery: using it showed you were a member of a group that understood those nuances. Using it conveyed ideas about what that group was and what being a member meant.

Mimbres villages from the A.D. 1000–1130 period have almost no other types of painted pottery, an unusual situation in the Southwest. Being part of what archaeologists call “Mimbres” meant choosing not to use the decorated (and symbol-laden) pottery from elsewhere. After 1130, potters stopped making this distinctive pottery. At the same time, almost everyone in the area moved (either short or long distances) and very rapidly incorporated pottery designs from other places into their lives.

Like many researchers, I think this meant people were symbolically turning their backs on an aspect of their past identities, and the new pottery styles were symbols of changed identities and new kinds of social connections. Perhaps the pottery’s symbolism had begun to be used in a way most users no longer saw as positive, or perhaps people no longer saw membership in the group it stood for as desirable or even possible.

Other pottery symbols are interpreted to stand for certain groups of people or social identities. In southern Arizona, researchers such as Jeff Clark, Deb Huntley, Brett Hill, and Patrick Lyons have demonstrated that Maverick Mountain pottery was used by a community in diaspora—a group that was spatially dispersed but had a shared culture. In southern Arizona, this pottery was used by immigrants from the Kayenta area (northeastern Arizona and southeastern Utah) in their new communities, and its symbolism was connected to that heritage.

A few generations later, Salado polychrome pottery was used in coalescent communities—culturally diverse groups of neighbors who shared social, economic, and political institutions. The multiethnic culture archaeologists call Salado used this pottery as a symbol of group membership, a symbol that united their diverse population under a shared identity.

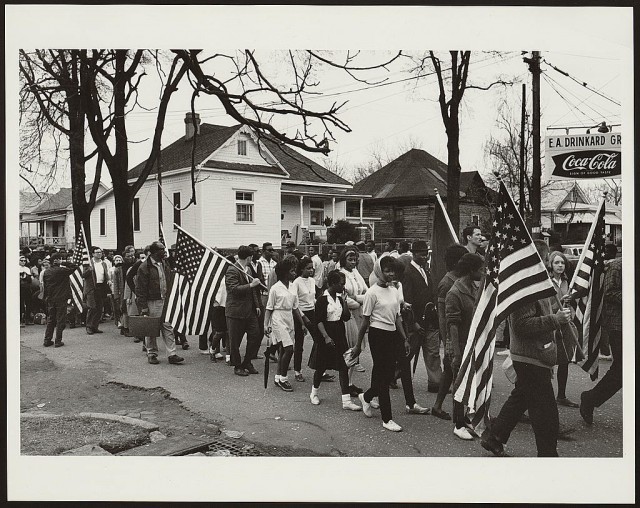

The American flag serves similar symbolic purposes today, albeit at a much larger spatial scale. It represents Americans of all backgrounds living in the U.S. (a coalescent community), and it is also a symbol of Americans living around the world (a diasporic community). It stands for a country and its people, but like any other symbol, it can be used by different groups in different situations and with different meanings.

To me, the American flag is a symbol of the ideas expressed in the last line of the Pledge of Allegiance we say when facing it—“liberty and justice for all.” It represents a nation whose core values are liberty and justice for every person. That is its power to unify. May it never lose that power.

![By USCapitol (House Chamber) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Click to enlarge.](https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Flickr_-_USCapitol_-_House_Chamber-640x421.jpg)